Against all odds

By Stella Katsipoutis-Varkanis

It was summer of 2000, and then-7-year-old Unique Andres ’15 had arrived at Palm Springs, excited to start her vacation with her aunt, uncle, and cousin. What she didn’t know was that, two hours after she had left home for her trip, her mother had died of a myocardial infarction.

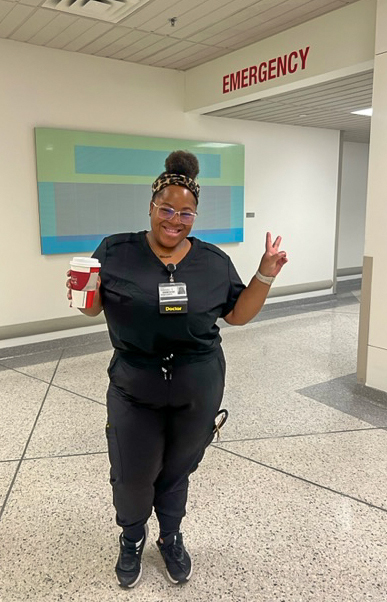

Unique Andres ’15

“I remember my cousin and I were playing in the living room of the timeshare, and my uncle had an eerie blank stare on his face,” Andres says. “The next morning, he brought me into a room where my aunt—my mother’s sister—was crying profusely, and they told me what happened.”

Andres soon moved in with her grandmother, Danny Kay Ross—a librarian at her new elementary school, Immaculate Conception in Monrovia, Calif. Only three months after her mother’s death, Andres noticed something odd about her grandmother during one of their daily walks to school.

“It was her turn to bring coffee to the office,” Andres says, “and every few steps through the parking lot, my grandmother would drop the coffee cans, pick them up, and then drop them again. That was the last time I ever saw her alive. When I got out of school that day, there was my aunt, who told me my grandma suffered a brain aneurysm.”

The child’s world was whipped around once more—and so was that of her aunt, Karen Little, who went on to adopt Andres. “It makes me emotional, because my aunt—now my mom—not only lost her sister and her mom, but now she had to take in a 7-year-old girl,” Andres says.

The two back-to-back tragedies made yet another life-altering impact on Andres: They ignited her dream of pursuing a career in medicine.

“As I got older, people asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up,” she says. “Not many jobs could have made a difference in those deaths. The only person who could have intervened and possibly saved their lives would be a doctor. That’s how I knew what I wanted to be.”

Today, Andres isn’t just manifesting that goal; she’s making history as the first Black female resident of the emergency medicine program at University of Iowa. Her mission: to increase representation of minorities in the medical field.

“Black physicians only make up less than 5% of all physicians in the U.S.; Black women only make up 2%. That’s the undeniable truth,” Andres says. “African Americans are underrepresented in general—there are so many things against us, like lower socioeconomic status. And if I, in some way, can make us a little bit more even, that’s what I want to do. My main goal in life is to pull up others with me as I go up.”

Andres says there also is something to be said for the immediate connection between Black doctors and patients.

Andres is proudly treating ER patients—and going down in the history books—at University of Iowa.

“It can’t be explained; it can only be felt,” Andres says. “I treat every patient with the same respect and give them my best. But there’s a sense of pride, a feeling of comfort you can only get from someone who looks like you, a sense of understanding and almost relief that this doctor is going to get it. In our culture, Black men notoriously are not allowed to show emotion. So, if a Black man walks into the emergency room, he might say he’s in a little pain when he’s actually a 20 on the pain scale. But that’s something you may not know unless you’re Black. Simply bringing a different perspective as a minority doctor helps, and that’s what I want to bring more of into this world.”

After her initial video interview for the residency at University of Iowa, Andres was unsure if the position would provide her the opportunity to treat diverse patients. That is, until she was contacted by Angie Wild—clinical assistant professor of emergency medicine and emergency department director of diversity, equity, and inclusion at the university—who invited Andres to visit the campus in person on diversity day.

“Knowing the Midwest is predominantly white, and having never been there before, I thought I would never get to see Black patients—which I found out is totally incorrect,” Andres says. “I had no clue 20% of the patients there are Black. It totally flipped it around for me when I saw how supported I would be if I were to work there.”

Andres also was impressed—and slightly intimidated—by the large, state-of-the-art emergency department, after having completed her core rotations in much smaller hospitals in New York City.

“I’ve seen the worst of the worst,” she says, “and the University of Iowa hospital was majestic. One thing Dr. Wild told me is that, being a minority, sometimes we feel like we have to struggle—like I have to be in the trenches to actually make a difference for my fellow minorities. But she said sometimes it’s OK to have nice things.”

It was at that point Wild also told Andres that, if she were to be hired, she would become the first Black female resident of the hospital’s emergency program. And that is exactly what happened.

“When I found out [I got the position], I just started crying,” Andres says. “That’s when it hit me that I was making history. But I also realized this big accomplishment comes with big responsibility. Now that I’ve opened the door, there’s a pressure I’m putting on myself to be great in order to keep that door open so another Black person can walk through it after me. I can’t just be average.”

The long list of things she’s achieved to date—in the face of adversity—unquestionably illustrates that Andres is anything but average. She has traveled unimaginable distances, both literally and figuratively, to arrive where she is today, and her journey to success has been as unique as her first name.

It began when Andres left her native state of California and headed to the East Coast to attend Lafayette College. She had first learned about Lafayette as a high school senior when Little was helping her research colleges to which she could potentially apply. After visiting the College several times thanks to the help of Carol Rowlands ’81, now-retired assistant vice president of enrollment management, Andres was captivated by the campus, Lafayette’s fostering of a diverse and inclusive environment, and a dazzling Precision Step Team performance she caught during one of her tours.

“I saw how the crowd respected them, and I thought to myself, I have to be on this team,” Andres says. “I also realized Lafayette was a place that was going to put me in the right spaces and give me the right resources to get where I needed to go.”

Despite being discouraged by her high school counselor—who told her she wouldn’t be accepted into any colleges that weren’t Black—Andres applied to Lafayette and was accepted with a full-tuition scholarship, and thrived as a biology major with a minor in sociology. She was a member of not only the Precision Step Team, but also the Lafayette Dance Team and the Association of Black Collegians (ABC). She also worked on campus as program coordinator of Portlock Black Cultural Center and as an athletic trainer.

“I really found my niche at Lafayette,” Andres says. “It’s where I met some of my lifelong friends. It gave me the opportunity to take unique courses like Medical Anthropology—which broadened my thoughts on how culture affects the practice of medicine—and study abroad and see the world. And its academic rigor prepared me for medical school by teaching me not to give up.”

Nancy Waters, associate professor of biology and faculty health professions adviser at Lafayette, she says, also played an integral role in her successful pursuit of medical school.

“Dr. Waters doesn’t feed you sugar cookies; she gives you the straight facts,” Andres says. “She knew I didn’t always have the best grades, but she believed in me, and she gave me the push and motivation to make it into medical school.”

Following her graduation from Lafayette, Andres took a two-year break to study for her MCAT and GRE exams. In 2017, she was Caribbean-bound to begin her studies at Ross University School of Medicine.

“There’s a lot of things that come with going to a Caribbean medical school,” Andres says. “It’s harder to make it out, because at every point there is a way for you to be kicked out. I failed my first semester—not because I wasn’t good enough, but because studying in medical school is different from studying in college. Ross had two grading systems—and if you fail either one of the two metrics, you have to repeat the entire semester. So, I repeated my first semester, and then the hurricane hit.”

That year, Ross University’s original main campus—which was located on Dominica—was devastated by Hurricane Maria, the worst natural disaster to sweep the Caribbean island. As the school had been essentially washed away, Andres and her fellow displaced medical students were relocated to a ship where they studied for three months before they were transferred yet again to facilities owned by Lincoln Memorial University in Knoxville, Tenn. They stayed there for one year while Ross built a new campus in Barbados, where Andres spent her last two semesters. In the meantime, Andres failed her third semester after battling through a bout of depression.

“Several of my family members were going through health issues at the time, and it was a lot,” Andres says. “Depression was something I had never dealt with, or never allowed myself to deal with, because it’s not something you talk about in Black culture. So, I failed again—and if you fail two semesters at Ross, consecutive or not, they kick you out. I got kicked out for a few days, but they let me back in immediately because, after the hurricane, they started letting students come back if there wasn’t a drastic reason for failure. My last three semesters, I got better and better. It’s like a switch had switched, and I had the highest grades I’d ever had.”

Andres had to clear another hurdle in 2019, when she became a caretaker for her father following a stroke—which he suffered at the same time Andres was preparing to take her first board examination. She took and passed her exam in 2020, “and we all know what happened in 2020,” Andres says. “I was out of school for seven months because of COVID, since they didn’t have a hospital for me to start my core rotations in. I didn’t start until 2021, which added on to the time I was in medical school. Even though I was supposed to graduate in May 2022, I didn’t graduate until November 2022, and I started my residency a year later than I should have.”

Though the timing didn’t turn out quite as she expected because of the speedbumps she encountered along the way, it was right nevertheless, as Andres is now proudly treating ER patients—and going down in the history books—during her first year at University of Iowa. Looking ahead, Andres sees herself continuing on as an emergency physician, but she also is contemplating pursuing an assistant program director role in the future.

“In order for me to bring more underrepresented minorities into medicine, that starts with me being on a residency committee and voicing my opinions, like Dr. Wild did for me,” she says. “You can’t bring more people to the table if you’re not at the table.”