Pay it Forward

By Heather Mayer Irvine

By Heather Mayer Irvine

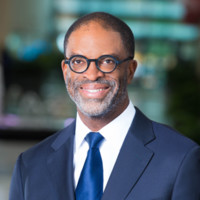

Today the Lafayette campus looks a little different than it did when Joseph “Ricky” Godwin ’81 made a name for himself. Back then, says Godwin, there were maybe 20 other African American students. But you knew where to find them.

“Our experience existed around one house,” Godwin says, “the Black House.”

Formally known as Association of Black Collegians (ABC), the Black House became an extended family for African American students, Godwin says.

Godwin attributes a combination of factors to his “first-generation success” story.

Lafayette recruited the Queens native to play basketball and offered him a full-ride scholarship. Godwin credits support from his friends at the Black House, his efforts in biology, and his interest and passion for math and science for the person and professional he is today.

Scholarships—athletic and otherwise—and programs like Posse help students who otherwise may not have the means to attend an institution like Lafayette, Godwin says.

“Most kids from Queens—middle or low class—couldn’t afford to go to a school [like Lafayette] without a scholarship,” he says. “Scholarships are important to give kids access to other parts of society they normally wouldn’t have experienced.”

Ricky Godwin ’81 pictured during the 1980 basketball season.

And sure, Godwin was a talented basketball player, but he’s not shy about his academic merit.

“If it hadn’t been for me being able to play basketball, Lafayette College never would have found a premed student called Joe Godwin,” he says. “I like to believe [the College] benefited from me being there like I benefited from being there.”

Ultimately, Godwin didn’t pursue a career in biology or medicine. But he’s found success in another passion: math and finance. He graduated from New York University Stern School of Business in 1994.

Godwin worked for IBM for a decade and a half and then worked his way toward Wall Street, something he had always wanted to do. Today, Godwin is a private wealth financial officer and managing director at Wells Fargo in Philadelphia. His clients include high-profile entertainers and athletes. Godwin takes pride in serving other first-generation success stories.

“The lion’s share of my professional athletes come from neighborhoods like mine,” he says. “And it’s not just black athletes. It’s people who aren’t born with a lot of distractions other than sports. That was the only thing they could afford to do. My background lends itself to people who have first-generation wealth.”

“The lion’s share of my professional athletes come from neighborhoods like mine,” he says. “And it’s not just black athletes. It’s people who aren’t born with a lot of distractions other than sports. That was the only thing they could afford to do. My background lends itself to people who have first-generation wealth.”

When Godwin graduated from Lafayette, he knew he was smart and could do whatever he put his mind to. And he wanted to pay it forward—literally.

“I wanted to do something that had a real impact on the world,” he says.

Godwin’s clients, he says, will never outlive their money—they have too much. So he works with them to make the most of their wealth.

“When I think about managing their wealth, I think about their legacy, their children, their ability to appreciate their wealth,” Godwin says. “I feel like I’m making a small contribution to the world by making [my clients] better people and more impactful.”

To say Godwin also tries to make a difference at his alma mater would be an understatement. In 2008 Godwin, along with several other African American alumni, started the McDonogh Group, as it was called then.

“A handful of us from ABC wanted to give back to the school in a more meaningful way,” he says.

The McDonogh Group, now the McDonogh Network, is named after David McDonogh, a slave whose owner wanted him to attend college. He graduated from Lafayette in 1844.

Godwin and his fellow alumni wanted to connect the African American alumni to each other and keep them involved with the College.

“I left college a little bitter,” Godwin admits. “I was connected to 20 people from the ABC house but not to the 2,380 other students on campus. But by having [the McDonogh Network] it helps people stay connected to the school.”

Plus, he says, when students of color find success after graduation and can contribute financially to the school, they’re helping other kids who look like them.

“You can help a class of 20 [African American students] grow to 200,” he says. “That’s a good thing.”