Purchase Tickets

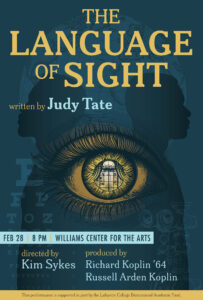

- The premiere of The Language of Sight will take place at 8 p.m. Feb. 28, at Williams Center for the Arts. Purchase tickets.

Richard Koplin ’64 brings David McDonogh’s story to center stage in new play

Richard Koplin ’64 P’91 (left), is pictured with artist, Melvin Edwards, and daughter, Russel Arden Koplin, at the dedication of the Transcendence statue at Lafayette in 2008. Melvin Edwards created the statue to honor David McDonogh 1844.

By Madeline Marriott ’24

Richard Koplin ’64 P’91 first encountered the story of David McDonogh, the College’s first Black graduate, two decades ago.

He was a member of the Board of Trustees educational policy committee, tasked with revamping the pre-med mentoring program and looking for a namesake when former college archivist Diane Shaw introduced him to the history of the little-known alumnus. Koplin was struck by McDonogh’s story. The more he learned, the more he discovered remarkable similarities between their respective paths.

“It was like he was my brother,” Koplin says. “We both attended Lafayette. I attended Columbia College. David McDonogh attended Columbia Medical School (though they refused McDonogh his M.D. degree), and John Kearny Rogers, the founder of the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, taught him ophthalmology in the very building where I’m currently co-chief of cataract services. If David walked through the door, I would feel like I knew him.”

The Language of Sight will premiere at 8 p.m. Feb. 28, at Williams Center for the Arts.

This connection kicked off 20 years of research on McDonogh’s story, culminating in Koplin’s production of The Language of Sight by Judy Tate, a play of McDonogh’s life, premiering on the Williams Center for the Arts stage at Lafayette in February. It tracks McDonogh’s unlikely journey from enslavement in New Orleans in the 1830s to becoming the country’s first Black eye specialist and his role as an abolitionist.

At every turn, those in power tried to keep McDonogh from achieving this feat. He had been sent to Lafayette College by New Orleans slaveowner John McDonogh with the agreement that upon graduation, he and another slave, Washington McDonogh, would emigrate to the nascent nation of Liberia through the auspices of the American Colonization Society. While Washington left the continent in 1842 as planned, McDonogh refused to follow suit until he gained a medical education. John—his only source of funding for his education—then cut him off.

With the help of Walter Lowrie, a senator and McDonogh’s guardian while at Lafayette, he graduated and made his way to New York. He was then introduced to John Kearny Rodgers, who convinced leadership at Columbia Medical School to allow McDonogh to attend classes. This time, however, university leadership refused to even confer his degree unless he agreed to go to Africa. Once again, he refused.

McDonogh learned the practice of ophthalmology under the wing of Rodgers himself, who brought him to the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary.

At the urging of Koplin and Diane Shaw, McDonogh was awarded a posthumous degree by the university in 2018, and a $1 million scholarship was established in his name.

“David’s personality was indomitable, as we’ve learned,” Koplin says. “He was a force to be reckoned with, and the play shows that.”

Koplin’s daughter, actress Russell Arden Koplin, is producing the play in collaboration with playwright Judy Tate and director Kim Sykes. A New Orleans native herself, Sykes attended a McDonogh school, a vestige of slave owner John McDonogh’s will that initiated the New Orleans school system in the 19th century. She only learned McDonogh’s full story after meeting Koplin and was drawn to the opportunity to combine her interests in theater and history in a new way.

“What the playwright is asking, and what speaks to me about this story, is the question of what it really means to see,” Sykes explains. “David is the bridge between science and social justice. He worked hard to help people physically see, but also to see the value and humanity of Black people. This was in a time when America was in the stronghold of the slave states, and decisions were being made around the country in order to protect slavery,” Sykes continues. “At the same time that Harriet Tubman was saving people through the Underground Railroad, David McDonogh looked around and said, ‘You know what? I’m going to become a doctor.’ It’s unheard of. It’s a superhuman feat.”

The play includes multiple episodes, jumping from the 1830s New Orleans of McDonogh’s youth to 1850s New York and even eras before his birth. It also imagines conversations between McDonogh and the Marquis de Lafayette himself, highlighting the connection between their respective missions.

By staging the play at Lafayette, Koplin hopes students and the Easton community can forge a deeper connection to their history.

“I was recently speaking to some students at a McDonogh event, and I told them that David was looking over their shoulders and expects big things from them,” Koplin says. “He expects this community to stand up for what he did, honestly and full-heartedly pursue their academics, and not be put off by the ways of the world.”

“If we don’t tell these important stories, we risk losing them,” Koplin continues. “I want this new generation to understand the importance of what happened at Lafayette all those years ago.”

As the team prepares for the first public staging of the play, they are looking forward to seeing McDonogh’s story touch audiences in Easton and beyond.

“We know what we have here is special, but part of the joy of theater is that you can’t do it alone—you’re dependent on everyone else who’s playing in the sandbox with you,” says Russell Koplin, who works closely with Sykes on the day-to-day logistics of the project. “We’re continuing to build it, and we’re excited to see where it goes after Lafayette, whether that’s Broadway, off-Broadway, regional theaters, or other colleges and universities where the story needs to be told.”