‘If You Want Change, You’ve Got to Create the Change’

By Shannon Sigafoos

Stan Morse ’85 believes that many people don’t understand the injustices and fundamental flaws of the public housing system and gentrification. He learned about those flaws growing up in Bedford-Stuyvesant (Bed-Stuy), a Brooklyn anchor of New York’s Black community for nearly a century.

“Being raised there, you are deeply impacted by the issues of your community. It’s a lot of poverty, a lot of gangs, a lot of drugs, and the issues we’re dealing with today such as police brutality. When I first got into public housing, they were nice spaces that were well maintained. Over the years, there was a disinvestment in public housing, and I saw the direct impact that had and how those nice developments became slums,” he explains. “That gave me a spark to say that you can fight back. You can change your environment and change your life.”

“Being raised there, you are deeply impacted by the issues of your community. It’s a lot of poverty, a lot of gangs, a lot of drugs, and the issues we’re dealing with today such as police brutality. When I first got into public housing, they were nice spaces that were well maintained. Over the years, there was a disinvestment in public housing, and I saw the direct impact that had and how those nice developments became slums,” he explains. “That gave me a spark to say that you can fight back. You can change your environment and change your life.”

Arriving at Lafayette College in the early 1980s was a culture shock for Morse, who was one of only two students recruited from public schools and one of few Black students on campus. Four decades ago, programs didn’t exist to identify and support Black students with academic and leadership potential—leaving Morse to figure out his own stepping stone to fitting into his new environment.

He found it came naturally to speak out and speak up against Apartheid, leading campus demonstrations against the system of institutionalized racial segregation that existed at the time in South Africa. It inspired him and others to put passion into action and to have a voice about issues that they saw were not fair.

It was the catalyst he needed for returning to his New York community post graduation with more awareness and an idea of how to help his struggling neighbors.

Grassroots Activism

“What are you going to do about it?”

“What are you going to do about it?”

Morse says this question was one that rang throughout the neighborhood he returned to in 1985. There was a lot of activism taking place in New York City, and Rev. Al Sharpton, a major figure in the civil rights movement, was coming into prominence. Local hip-hop and rap musicians, including Morse, used their lyrics to vent their feelings and frustrations about what was happening in the world around them. Then, at 28, he was asked to channel that energy into running for city council.

“I didn’t know anything about politics or how politics works,” he says. “I was kind of idealistic.”

Knocked off the ballot by those who didn’t want grassroots activists involved in the local political arena—a situation he felt protected the status quo—the bitter taste left in Morse’s mouth meant it would be a number of years before he would become politically active again.

“There’s a big difference between activism and being a politician. Activism is really representing those who have been locked out of the system and those who have been ignored,” says Morse, who has now been in grassroots activism for over a decade and has seen Bed-Stuy become heavily gentrified. “We have all this development, all this growth, and we have people living in subhuman conditions. There’s something dramatically wrong when you see this cycle happening over and over.”

When he began organizing in Long Island City, Morse saw residents of the Queensbridge Housing Development—the largest housing development in the country—living in squalor and going without repairs at the same time Amazon would have received over $3 billion in government incentives to build there in 2019. He was one of many who were fiercely vocal about the impact on the local neighborhoods, particularly for those who were promised new jobs but didn’t have proper training for them.

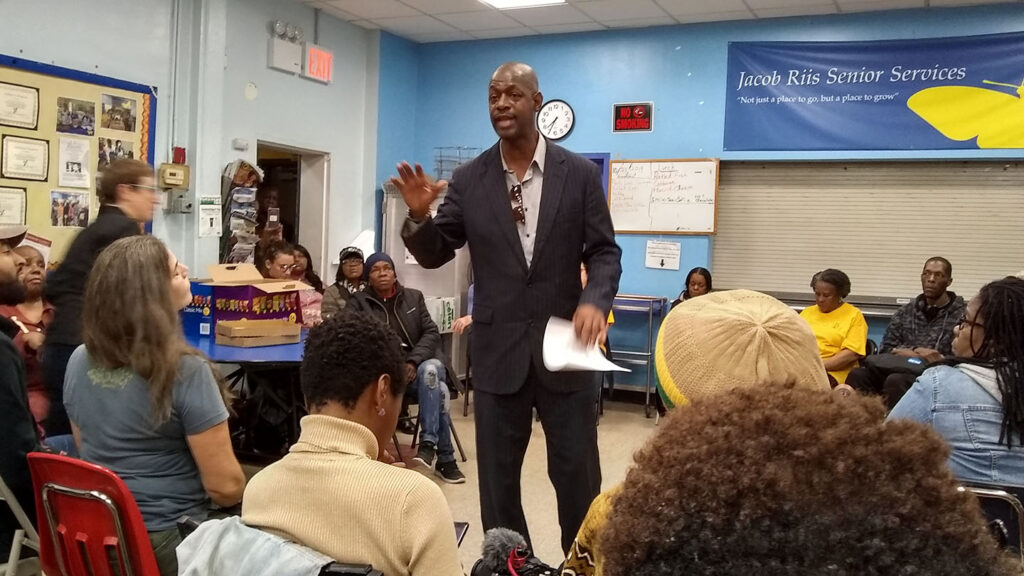

Today, Morse is lead organizer for the Justice for All Coalition, which was formed in Astoria and Long Island City to address community needs around rezoning efforts. The group’s mission is to inform, educate, and organize the community to become united around a shared vision, and be proactive regarding quality-of-life issues.

Today, Morse is lead organizer for the Justice for All Coalition, which was formed in Astoria and Long Island City to address community needs around rezoning efforts. The group’s mission is to inform, educate, and organize the community to become united around a shared vision, and be proactive regarding quality-of-life issues.

His days and nights have been spent helping other residents rally for repairs to their homes, planning rent strikes, and avoiding evictions. It is a never-ending process, keeping Morse and other volunteers on long phone calls and in (virtual) meetings throughout the COVID-19 crisis as they’ve watched many already suffering with quality-of-life issues succumb to the pandemic.

“If I told you the stories, you would cry … because people are actually dying,” says Morse. “We’re in a situation now where we cannot afford to have the same type of politics.”

Run for Politics and the Lafayette Connection

High-rise developments driving profit for real estate companies. Out of control rent. Homelessness plaguing the city. All of these issues led to Morse doing the one thing he never expected he would do again—throwing his hat in the political ring.

Morse is currently campaigning for the Queens Borough Presidency, with a policy platform guided by the values of community justice and wellness. He is heavily focused on the Black, brown, and working-class communities bearing the brunt of bad policies, and has laid out a plan to address housing insecurities, displacement, educational opportunities, employment, and physical threats to hyper-policing.

“If you want change, you’ve got to create the change that you want to see,” he says. “In Queens, there is a push for change that can actually upset the natural order of things. I have a unique experience as someone who has seen it from childhood all the way to my age. I think people are tired of our politicians because they don’t really know where they stand. We’ve laid out very clearly on our website what our plans are, and we’re going to transform this broken system.”

“If you want change, you’ve got to create the change that you want to see,” he says. “In Queens, there is a push for change that can actually upset the natural order of things. I have a unique experience as someone who has seen it from childhood all the way to my age. I think people are tired of our politicians because they don’t really know where they stand. We’ve laid out very clearly on our website what our plans are, and we’re going to transform this broken system.”

During his campaign season, Morse has reconnected with students at Lafayette and has made time to listen and give them advice about getting involved now in issues that they’re passionate about. After all, that first spark of activism for him was lit during his time at the College.

“I just had an hour-long conversation with [student] Devin On ’22. He’s on the football team. He’s a Posse Scholar. And he’s from the South Bronx. He really related to my story of coming from Brooklyn and going to Lafayette,” says Morse. “I was really impressed by his level of understanding of what’s happening in his own community, seeing it redeveloped. I’m also blown away by the list of demands that Lafayette students have made in regards to the Black Lives Matter movement. We need students like that to continue to want to make change in their communities. It’s going to deeply impact their lives.”